Encrypt it

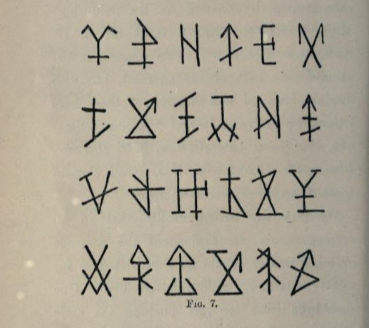

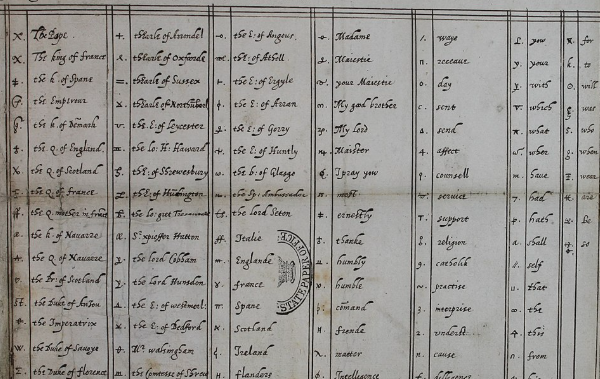

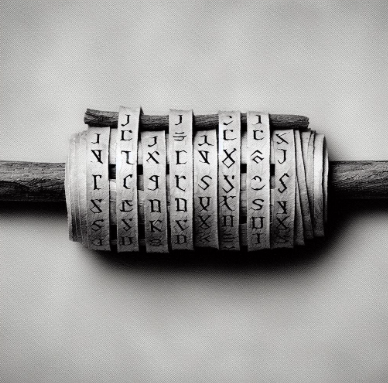

Cryptography goes back thousands of years. From Ancient Greece to the end of World War II, it was mostly used for military communication. After WWII, its scope was expanded to include protecting business and personal information while evolving technology allowed, and continues to allow, for increasingly complex algorithms.